Ethanol: The Invisible Fuel

I was recently waiting in line at a car rental counter and happened to overhear the conversation between the customer in front of me and the rental agent. The customer was concerned about the gas mileage of the rental pickup truck he was being assigned. The agent assured him that the gas mileage was very good, and began describing how it was a “flex-fuel” vehicle, and this meant that it did not idle while at a stop. None of this information was accurate, however the customer was satisfied with this response and went ahead with the rental.

I realized in witnessing this interaction that while flex-fuel vehicles have been on the road for over two decades now, the average driver may be relatively unaware of what that means, or what ethanol blending into gasoline is and why we do it in the first place. After doing some digging, I realized there is a lot to dive into here: In this post, I’ll talk about ethanol as a fuel. In the next post, I’ll dive deeper into the rise of flex-fuel vehicles, which is arguably far more interesting.

To get started, there are two main topics that come up when discussing ethanol as a fuel:

- Ethanol use as an oxygenate additive to gasoline

- Ethanol use as a fuel itself

I will discuss both of these in depth and hopefully address some of the misunderstanding arising from the ethanol debate.

Why is ethanol in our fuel supply?

To understand why ethanol was initially introduced into the fuel supply, I will first discuss its use as an oxygenate additive. Prior to 1975, refiners added lead (really, tetraethyl lead) to gasoline as an antiknock agent. Knocking in an engine occurs when the gasoline ignites too early, before the correct compression has occurred in the cylinder and before the spark plug has ignited the air/fuel mixture. Because knocking damages the engine, fuel providers began blending antiknock agents into fuels in the 1920s. These agents increase the octane of the fuel, reducing knock. After the discovery of lead’s detrimental effects, as well as the rise of the catalytic converter (and lead’s incompatibility with catalytic converter components), chemists began coming up with alternatives.

Beginning in 1979, the most widespread alternative was a chemical called MTBE, an oxygenate, or material that increases the oxygen content of fuel. Amendments made to the Clean Air Act in 1992 drove further commitment to the chemical because it reduced the carbon monoxide production of gasoline. However, due to MTBE’s high solubility in water, the chemical was making its way into water supplies at a noticeable rate. Leaks from fuel tanks resulted in contamination of soil and water, and while no ill effects of the chemical are known, the high solubility was problematic enough that a transition to yet another alternative became attractive. By the mid-2000’s, many states had banned MTBE completely.

Enter ethanol. At the time when refiners shifted away from MTBE, ethanol was known as the next substitute. Now, an important point is that ethanol’s preeminence in the fuel market today is not driven solely by refiners: Legislation has created the fuels we use today. Of course, once demand for ethanol increased, many farmers took note and increased production to establish themselves in this new market.

Around this time, the mid-2000s, gasoline prices were rising rapidly and the national issue was of interest to politicians. Blending American-made ethanol into fuel reduced the amount of gasoline required in each gallon of fuel sold, and thus increased the US’s fuel security. The Renewable Fuels Standard (RFS) was established as part of the Energy Policy Act of 2005, and sets targets for the amount of biofuels blended into the total fuel pool each year, shown in the graph below. This displacement of gasoline with American-made ethanol led to the 10% ethanol composition in gasoline that we see today. Had this shift not occurred, the United States would be consuming close to 11 billion more gallons of gasoline annually.

It is worth noting that the United States is not the only country that fuels with ethanol. Brazil, the second largest ethanol producer, has been using ethanol as a fuel for over 40 years, and there are no longer any light-duty vehicles operating in the country that run solely on gasoline. Currently, ethanol is mandated to be 27% of the fuel blend, far higher than in the U.S. The country’s ability to generate such a large volume of ethanol arose from the large amount of arable land and the innovation of efficient production processes. Because ethanol feedstocks can compete with food supply, there is also a debate about whether using food as a fuel impacts food costs. I will not go into it here, but there is much discussion and debate on the topic.

How does ethanol blending work and why are refiners OK with it?

The regulations do allow for refiners to adjust their blending activities as they need to still meet fuel specifications, which can result in less than 10% ethanol in fuel available at some gas pumps. Ethanol blending into gasoline is tracked through Renewable Identification Numbers (RINs), which are similar to Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) that utilities use to track renewable energy, as I discussed in an earlier post. RINs are generated by renewable fuels producers like ethanol manufacturers and are released once blending occurs. They can then be traded and/or retired as needed to meet requirements set forth by the Renewable Fuels Standard.

Why might a refinery choose to not blend the full 10% ethanol? As I mentioned above, octane is a critical specification of gasoline. One of the key processes that occurs during oil refining for gasoline production is naphtha reformation, which produces high octane feedstocks for use in the final fuel blend. Reforming takes medium-sized chains of hydrocarbons and turns them into rings. Because ethanol contributes an octane of ~110 to the final fuel blend, (recall regular gasoline has an octane of 87 and premium gasoline has an octane of 93..we won’t get into RON and MON and all that stuff here, though) refineries must blend gasoline components in a way that ideally hits the octane target as closely as possible without going over. “Octane giveaway” is costly: Producing high octane components through reforming is extremely energy and resource intensive and refiners take great steps to avoid what is essentially selling octane at a discount.

However, if a refinery configuration produces fuel components with octane levels that are too high (and/or if ethanol prices are high), the refiner may opt to forgo some ethanol blending and instead purchase RINs to meet the renewable fuel requirements. This ensures that the the renewable fuel is still produced and blended, but by a different entity.

As the price of gasoline has fluctuated over the past 15 years or so, and as the United States has become a major oil producer, ethanol has maintained its foothold in our fuel supply. In fact, in 2017, 81% of the US’s fuel needs are met with its own supply, while 19% was imported. As you may have already deduced, there are a few potential reasons why ethanol has maintained its marketshare.

- At 16 billion gallons per year, ethanol is now a big business. Suggesting relaxing regulation to allow for less ethanol in gasoline blending would result in significant political pushback.

- As mentioned above, the high octane value of ethanol contributing to the blending pool means that refiners can operate their plants at a reduced severity, reducing operating costs. If ethanol were not in the fuel blend, refiners would need to increase processing of some gasoline components, thus increasing energy consumption and reducing catalyst life.

- When ethanol production is strong, pricing can be attractive to oil refiners. Oil companies buy ethanol, blend it immediately into gasoline, and sell it at the price of gasoline (which should theoretically be priced as a gas/ethanol blend). There is no additional processing required, which means that oil refiners can make a good margin in certain environments. The graph below shows how the monthly prices have varied over time. In the beginning of 2018, the most recent data available, refiners may have been making more than $0.50 for every gallon of gasoline replaced with ethanol in the fuel blend. For a medium-sized refinery, that could equate to over $100,000 per day in additional profit, since the plant is simply mixing it in and selling it as gasoline. Thus, somewhat counterintuitively, refiners may also be averse to any changes in the ethanol regulations.

What does ethanol blending mean for the environment, and for me as a fuel consumer?

Now that we’ve gone over how the market for ethanol came to be, we should discuss what it means for the consumer - and the environment. There are a couple of key points to make when discussing ethanol as a fuel: Its renewable designation and how it performs as an alternative fuel.

Ethanol is indeed a renewable fuel - most ethanol is produced from sugar or starch-based sources. However, this does not necessarily mean that it is zero carbon. The graphic below from the EERE (Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy at the Department of Energy) shows that there is a wide range of results when researchers have compared the energy used to produce the ethanol to the energy in the ethanol itself.

Some studies have shown that more energy is required to produce ethanol than is contained in the fuel itself (negative value, falls below the axis), whereas most of the studies show a net positive energy value. It would be a pretty interesting investigation to dive deeper into how these studies may have been motivated, and whether some were financed by oil and gas or agro-industry interests. However, for this analysis, I will use a recent report done for the USDA (with this factsheet summary), which found that on an energy equivalent basis, ethanol’s lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions are 43% lower than gasoline’s. So even with the large amount of processing required to produce ethanol, the total emissions from production and combustion are lower than that of producing and combusting gasoline.

You may have also noticed, or heard the argument, that ethanol is not as energy dense as gasoline, meaning that your car running on 100% gasoline will experience higher gas mileage than your car running on 90/10 or 15/85 (the “flex-fuel” blend) gasoline/ethanol. Ethanol provides 35% less energy during combustion than gasoline, meaning you would need 35% more of it to go the same distance when compared to 100% gasoline. This is why when we discuss comparisons between gasoline and ethanol we must discuss them on an “energy equivalent basis,” where we look at each fuel per unit of energy, rather than per unit of volume. This energy difference is one reason why high ethanol blends (85-100%) offered at some gas stations appear to be cheaper than gasoline. Lower taxes on ethanol and other state incentives can contribute to the price difference as well.

In case you were curious, the estimated mileage difference between 100% gasoline and 90/10 gasoline/ethanol is only 3%, meaning that it is highly unlikely that you would notice a difference in your car’s gas mileage between the two fuel blends. Driving behavior itself will have a larger impact on gas mileage than this small amount of ethanol.

If ethanol is already in our fuel, why all the flex-fuel vehicles on the road?

Taking all of this together, we can begin to understand why the Renewable Fuels Standard came to exist, but why has there been such a dramatic rise in flex-fuel vehicles on the road?

Flex-fuel vehicles are nearly identical to the typical vehicle, but with slightly different engine tuning. This slight difference allows the vehicle to use fuel that contains up to 85% ethanol, or “E85”. Manufacturers offer these vehicles at the same price as the traditional gasoline car.

Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards have stipulated vehicle fleet gas mileage standards since the oil embargo and subsequent spike in energy prices of the 1970’s. Up through 2019, the rule states that ethanol has 15% of the emissions of gasoline (1 gallon of ethanol counted as 0.15 gallons of fuel), and that car companies can count E85 vehicles towards their standards, regardless of whether those vehicles were actually running on E85 or not. Beginning in model year 2020, manufacturers must calculate flex-fuel vehicle emissions using actual data on E85/gasoline sales or use, rather than assuming all drivers are opting for the ethanol fuel.1

Thus it is easy to see that car manufacturers were using flex-fuel vehicles to help their overall fuel standards, since consumers knew no difference (flex-fuel models do not cost any more or less than the traditional vehicle to purchase). With regulations changing to prevent continued reliance on flex-fuel for meeting standards, the rules should have forced vehicle manufacturers to continue to increase their fleet average fuel economy higher through other means, irrespective of whether flex-fuel vehicle owners actually used ethanol. I will dive into this in the next post.

It turns out that in 2017 there were over 22 million flex-fuel vehicles on the road, about 8% of all registered light-duty vehicles in the US. By comparison, since 1999, 4.6 million hybrid electric vehicles have been sold in the US, so we can assume far fewer than 4.6 million are still on the road today. However, with only 4,500 E85 fueling stations in the US (out of approximately 150,000 gas stations), it would be a stretch to think that many of those flex-fuel vehicles are actually running on E85. Combine that reasoning with the fact that the country consumed 119 billion gallons of gasoline and 15.8 billion gallons of ethanol as fuel, where ethanol represented 12% of the total fuel sold, only slightly higher than the 10% blended into most gasoline. One source suggests that only 38 million gallons of E85 was sold in 2016, which corresponds to 0.2% of all fuel ethanol ending up as E85.

What impact has ethanol as a fuel had on our environment?

More flex-fuel vehicles running on E85 rather than gasoline would certainly benefit our environment, assuming that the USDA emissions calculations are correct. Because the RFS essentially determines how much ethanol is produced (thus determining how much production capacity exists), and because the additional E85 demand just isn’t there (few flex-fuel vehicle owners are actually using E85), it is unlikely that there will be much of a push for additional E85 consumption. Despite this, ethanol blending into gasoline that already takes place eliminates a huge amount of emissions.

For reference, the average passenger vehicle emits 4.6 tons of carbon dioxide per year (22 mpg, 11,500 miles driven/year). The amount of CO2 avoided from the blending of ethanol is equivalent to removing 12 million cars from the road. That seems huge, but with over 272 million vehicles on the road, it is only 4% of the total. But it is still something! A summary of all of the background data for performing these calculations is shown in the table below.

| Summary (2017) | |

|---|---|

| Ethanol sold (gal) | 15,845,000,000 |

| Gasoline sold (gal) | 118,999,751,600 |

| Ethanol in fuel supply | 12% |

| Gasoline Heat Content (BTU/gal) | 114,000 |

| Gasoline Carbon Intensity (gCO2e/MMBTU) | 98,000 |

| Ethanol Heat Content (BTU/gal) | 76,100 |

| Ethanol Carbon Intensity (gCO2e/MMBTU) | 55,731 |

| Gasoline not consumed due to ethanol (gal) | 10,577,232,456 |

| CO2 avoided (tons) | 56,182,753 |

A few words about what our transportation future may look like

The ideal transportation picture is a difficult and complex one, one that requires many additional considerations than simply what is best for the environment. But if we narrow our focus and look only at what options are available to consumers today or in the near term, what are the best options?

While ethanol fueling infrastructure is sort of available since it uses much of the same facilities as our existing gasoline fueling stations, expanding it much further does not seem like it would be attractive to many consumers. Considering that almost 10% of vehicles on the road already can consume this alternative fuel and most of them don’t, and because understanding the price difference between gasoline and ethanol can be tricky, especially considering the shorter range of a tank of ethanol, it would be a challenge to change peoples’ minds about ethanol. In most cases, the cost of fueling with ethanol is nearly the same or higher than fueling with gasoline, meaning that the only value proposition provided by ethanol is that it is more environmentally friendly. As we know, that’s not enough for most consumers.

There are other alternative fuel options that have made an appearance, like compressed natural gas (CNG) and hydrogen, both of which would require significant infrastructure change in order to be widely useful to the average consumer. Deployment of CNG vehicles has been confined to those that fuel at a single location, such as delivery vehicles and buses (which are both, in general, huge fuel consumers). These fuels would require significant investment and incentives in order to be widely adopted. And we would expect that oil industry lobbying would not make any of this easy.

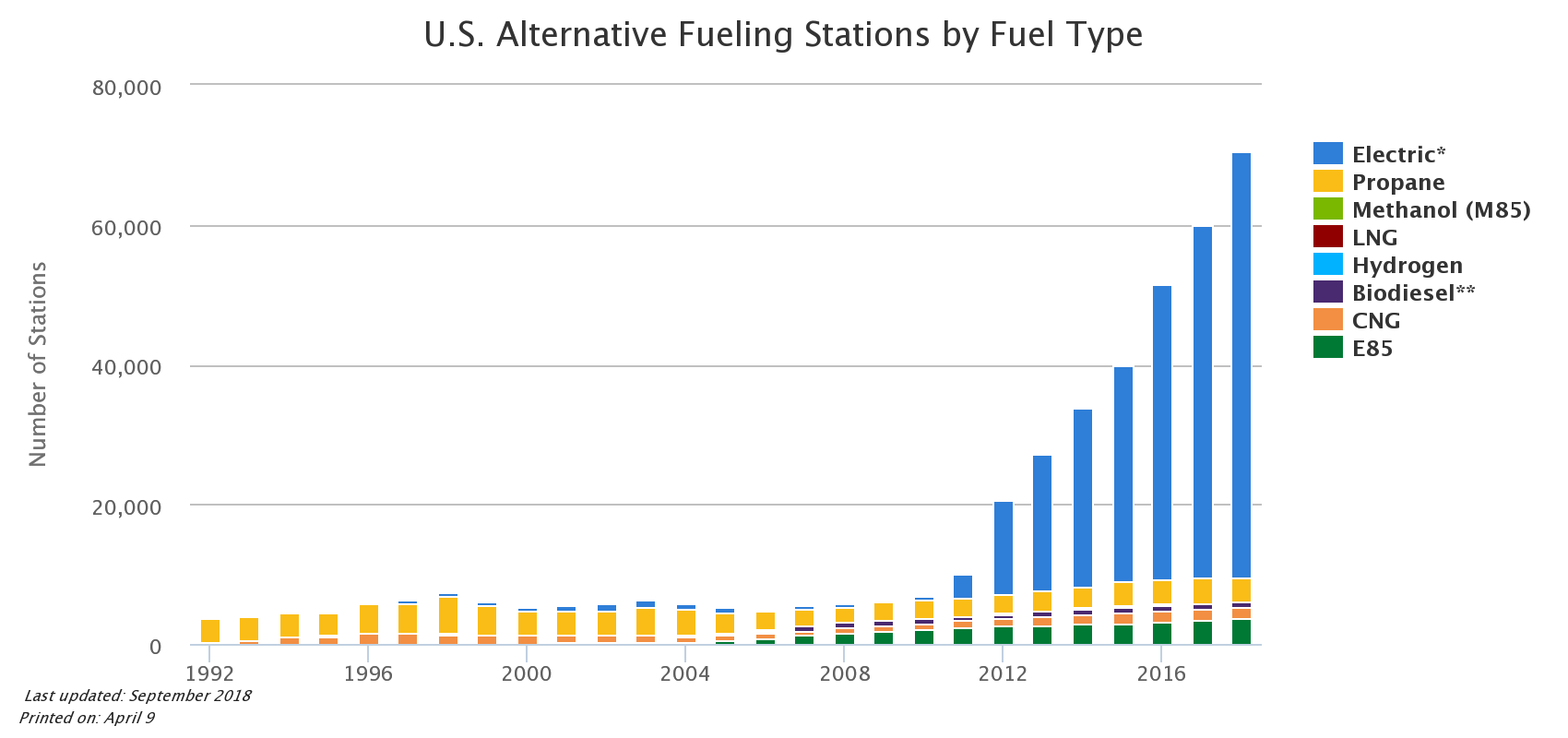

All of this has likely contributed to electric vehicles’ (EV) relative success in the marketplace. The existence of electricity infrastructure nearly everywhere means that creating a charging station is not as significant of an investment as a new liquid fueling station. EV owners can even have what is essentially a fueling station inside their own garage. For errand-running and day trips, this means that the EV user experience is nearly the same as the gasoline user experience, minus the trips to the gas station. The price of electricity is also much cheaper than gasoline, meaning that the EV itself can cost a bit more and the customer will still break-even. There are also still plenty of incentives in place for customers choosing EVs in many states.

The graphic below from the Alternative Fuels Data Center shows that the electric vehicle charging infrastructure picture is rapidly changing as well. One note here: While Tesla and their superchargers get a lot of press, they represent only a tiny fraction of the public electric charging stations in the country. Most of the stations are built and operated by third party firms, with the largest being ChargePoint.

In the end, federal and state government incentives, mandates, regulations, and rules largely dictate our vehicle market, what is available, and at what price. As the example of ethanol in gasoline made clear, influential interests on all sides have a huge impact on how widely and rapidly things may change. We can expect that the shake-up in transportation is far from over, and the customer may ultimately benefit. More options mean more competition, and the fight is far from over. It will be interesting to see how things have changed in just a few more years.

-

This section was updated on April 30, 2019 to fix an error. ↩