Alternative Fuels & the (Re-)Emergence of EVs

In my previous post, I discussed the introduction and rise of ethanol as a fuel in the US, and the impact on carbon emissions that it may have had. I touched on the topic of flex-fuel vehicles (FFVs), and expressed an interest in getting to the bottom of what led to their ubiquitousness in the current pool of vehicles.

As I noted in the post, nearly 10% of cars on the road can be fueled with E85, however there are only 4,500 stations across the country that offer it. By contrast, there are approximately 150,000 gas stations. We can probably safely assume few FFV owners are actually fueling with E85, and as a result, we are not achieving the carbon reduction benefit that those FFV models, at least in part, were intended to provide. This led me to the broader question of what, or who, determines the vehicle choices put before us as consumers, and do we even have much of a say? And what does the growing popularity of electric vehicles (EVs) mean?

There have been and continue to be many different interests that come into play in determining what vehicle technologies and body-styles are on offer to consumers. Some of these interests include oil companies, car manufacturers, politics/regulation, and consumer preference. All of these interests end up being intertwined, and it is difficult to separate which group really benefits from each argument, since one group can claim another is harmed by excessive or permissive regulation. A high-level review of the key stakeholders is helpful in understanding what may have shaped the current state of regulation. In addition, observing the recent history of the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards, which led to the rise of FFVs, is an interesting case study in understanding what the future technologies may look like.

Many interests at play

In considering this topic, I came to conclude that while there are many interests involved, the selection of vehicles on offer to consumers is largely driven by what car companies prefer to produce to maximize their earnings. While consumer preference is often mentioned as a leading motivator, car companies have significant influence over preference in the first place. After all, if you need a car, you aren’t going to wait around until the perfect one is available. You’re going to shop around what is available and pick the one that best suits your needs, even if it isn’t perfect for you.

One major factor in a consumer deciding on a vehicle is the price, and car companies know this. We have all seen the car advertisements that state lease prices, 0% interest rates, “zero due at signing,” and other financial incentives. A customer may be willing to make concessions in one area or another in order to pay less for a vehicle, particularly if they perceive that they are getting “more car for their dollar,” as could be the case with larger vehicles, like SUVs. This is just one example of how the auto industry may really be driving consumer preference.

The other side of the tug-of-war here is the regulation, and designing policy that does not discriminate against one group over another is no easy task. A few ways federal regulators have thus far managed and balanced the differing interests is through many, many different rules and regulations, each with its own focus on either the supply or the demand side of the equation. A few of the big ones to call out are:

- CAFE standards essentially lead car manufacturers to take responsibility for a greater proportion of the lifecycle cost and environmental and economic impacts of operating a vehicle, while also promoting alternative fuels.

- Tax incentives promote alternative vehicle ownership by consumers.

- The Renewable Fuels Standard has led to new products being made a part of the overall fuel pool.

Car manufacturer interests

Going deeper into what motivates car companies, a few things stand out. Consumer taste of course, although as I just discussed, this can be manipulated by what is on offer and at what price. Margins and sales volumes are certainly important, as is increasing or ensuring consistent demand, through attractive features like new technologies such as safety and collision avoidance systems. Ultimately, management of most companies, both within and outside the auto industry, is driven by what is best for the shareholder, which means that management will make decisions that maximize earnings, in order to increase stock prices and overall firm value.

Car manufacturers make a higher margin on SUV and crossover vehicles than they do on sedans or small economy cars. SUVs and crossovers are less fuel efficient than lighter, smaller, more aerodynamic vehicles, but, conveniently for car companies, the CAFE standards are also less strict. Today’s CAFE standards include two separate standards for light duty vehicles: One for short and one for long wheelbases. Long wheelbases mean that the total footprint of the car is larger (vehicle width * wheelbase = footprint). A larger footprint car has lower MPG targets than a car with a smaller footprint. There is also a distinction between passenger cars and light duty trucks, with many SUVs falling into the truck segment. As a result, car manufacturers are likely balancing many different factors to meet CAFE targets at the least cost, which likely means maximizing high margin, large footprint vehicles.

Through this simple example, we could see how auto manufacturers may be incentivized to promote slightly different models than what one might at first think when considering the CAFE standards. In fact, VW argued in 2011 that creating two categories, each with their own targets, would result in firms producing and heavily marketing larger SUV and light trucks, negating any effort to reduce overall emissions. And while we can probably agree that VW might not be the most honest voice when it comes to vehicle emissions, the argument may still have merit. Past calculations from the University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute suggest that average fuel economy of cars sold each model year hasn’t improved since 2014. The fact that Ford recently announced that it will no longer produce sedans (although they are hoping to introduce 16 battery powered models by 2022, which is when the next round of CAFE standards would start) seems to be in line with manufacturers continuing with strategies focused on larger, heavier vehicles.

Fuel economy technology

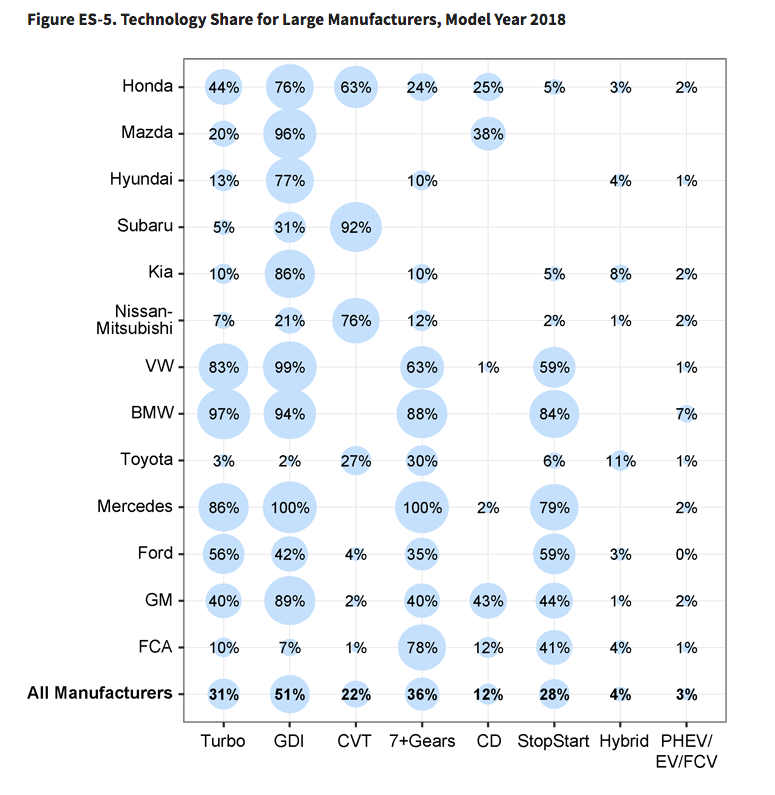

As CAFE standards have become stricter, all carmakers have begun focusing on “new” technologies within their fleets. Turbochargers, for example, while perhaps more commonly known for providing added power and speed to sporty cars, can also provide added power to small engines, allowing a heavier car to be fitted with a smaller engine, reducing its fuel consumption. However, this added equipment leads to added cost, which may have been the reason why some automakers held off on this strategy until more recently, once they were essentially forced to upgrade some standard technology in order to achieve the CAFE targets. Below is an interesting graphic from the EPA that shows which technologies each major manufacturer is leveraging most heavily. Unfortunately it does not include FFV or other dual-fuel technology.

GDI: Gasoline direct injection; CD: Cylinder deactivation; CVT: Continuously variable transmission; PHEV: Plug-in hybrid vehicle; FCV: Fuel cell vehicle

GDI: Gasoline direct injection; CD: Cylinder deactivation; CVT: Continuously variable transmission; PHEV: Plug-in hybrid vehicle; FCV: Fuel cell vehicle

There is discussion included in the EPA’s full report that details the rise and subsequent fall of FFVs in accordance with the changing regulation that we’ll go into in a minute. It suggests that because it was cheap to implement, flex-fuel technology became the go-to for some manufacturers, particularly on large SUVs and trucks. As the regulation changed and FFVs were no longer beneficial to the MPG calculation, manufacturers adapted and stopped offering as many flex-fuel models. This is what we’ll dive into a little deeper now.

Analysis - Alternative fuel technology

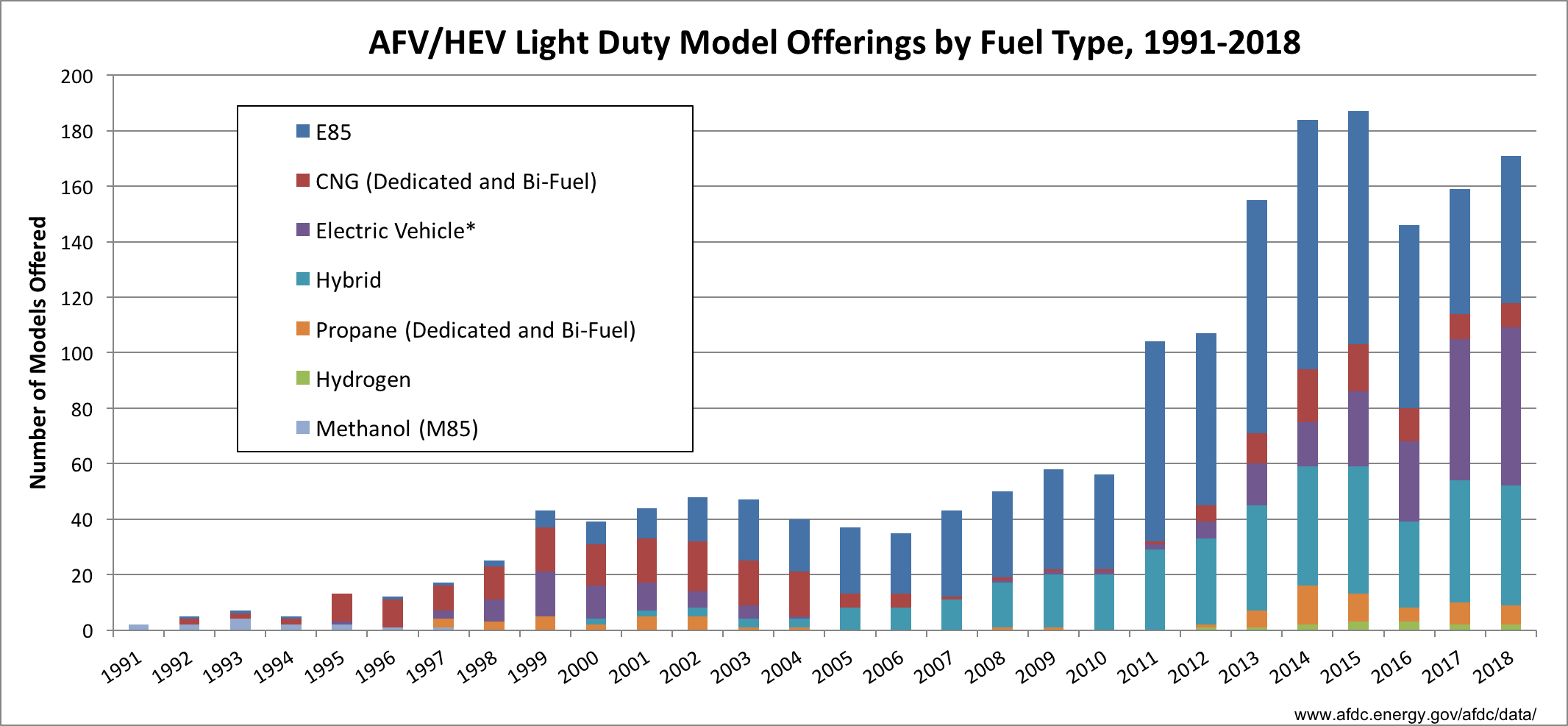

To better understand what the vehicle technology picture may look like in the future, it helps to look holistically at what the portfolio of vehicles has looked like in the past in the context of the changing regulations. If we go back in history and observe what technology has been on offer for customers interested in alternative fuels, we get the figure shown below.

EVs include plug-in HEVs, but do not include Neighborhood Electric Vehicles, Low Speed Electric Vehicles, or two-wheeled electric vehicles. Only full-sized vehicles sold in the U.S. and capable of 60mph are listed.

AFV: Alternative fuel vehicle; HEV: Hybrid electric vehicle

EVs include plug-in HEVs, but do not include Neighborhood Electric Vehicles, Low Speed Electric Vehicles, or two-wheeled electric vehicles. Only full-sized vehicles sold in the U.S. and capable of 60mph are listed.

AFV: Alternative fuel vehicle; HEV: Hybrid electric vehicle

We see compressed natural gas (CNG) with an early start, followed by electric and E85 vehicles. Manufacturers were heavily incentivized to pursue alternative fuels in the early stages of the CAFE standards. Multipliers were put in place that enabled car companies to leverage technologies like CNG or E85 fuels to drive their MPG calculations higher. We see that by the mid-2000’s, the number of E85 models available really takes off. The early introduction of EVs around 1997 and their subsequent disappearance for many years is a curious development, one that was likely influenced by each of the interests discussed above. It is also the topic of a 2006 documentary Who Killed the Electric Car, currently available for streaming on Prime, and is worth watching if you are interested in learning more. EVs then re-emerge in force in 2012.

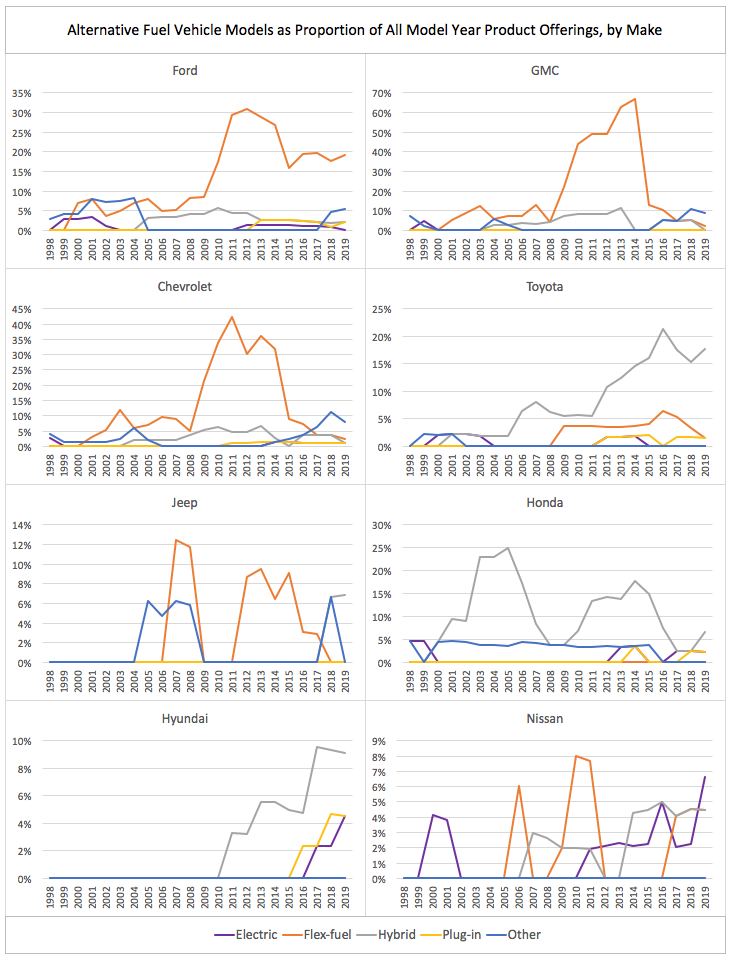

But what did the offerings of some of the biggest manufacturers look like over time? The figure below picks out a couple to look into in more depth.

Data source: https://www.fueleconomy.gov

Data source: https://www.fueleconomy.gov

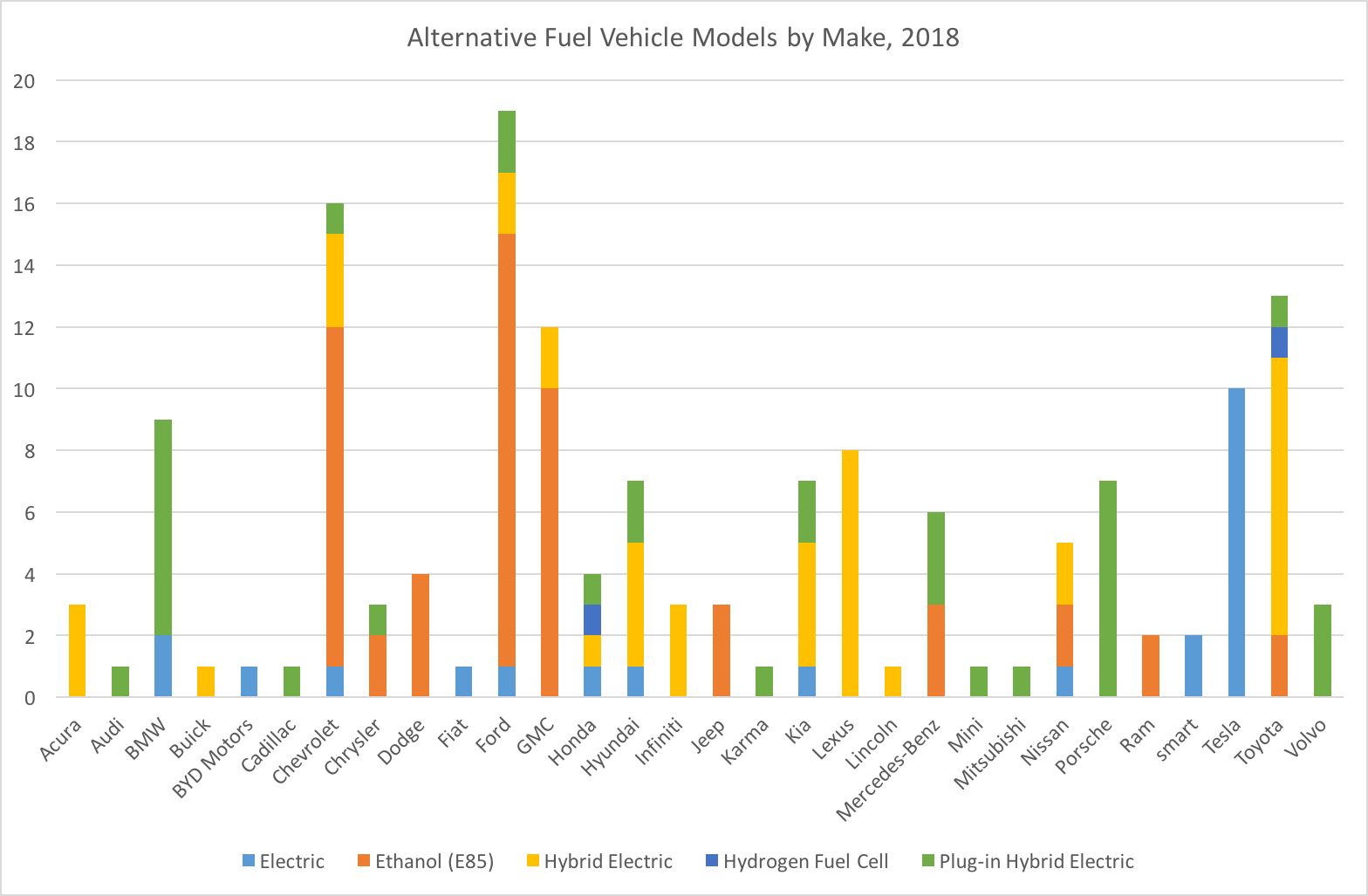

We see here how differently each automaker approached the CAFE standards. Some, because their existing fleets consisted of small, innately fuel efficient models, did not begin offering alternative technologies until much later than others, as the targets continued getting harder to hit and the cost of different technologies came down. Others, like the big American automakers, relied heavily on FFVs, and, by comparison, have few electric or hybrid vehicles. Toyota, Honda, and Nissan, in contrast, have, throughout this same time period, marketed hybrid vehicles. Nissan, with the introduction of the Leaf in 2011, appears on the electric car scene and has only increased the number of configurations of the Leaf technology since. It is worth noting that auto companies with small market share that tended towards niche sport vehicles (Porche, Mercedes, Fiat, and others) chose to pay the fines rather than comply with the regulations. Others that were able to overshoot their MPG targets generated credits, which can be used in future years or traded to other firms.

The number of FFVs has taken a nosedive since around 2015, likely driven by the calculation change in the CAFE standards. Up until 2015, the rule incentivized companies to pursue alterative fuels, and car companies could count E85 vehicles towards their standards, regardless of whether those vehicles were actually running on E85 or not. A 0.15 multiplier was put in place for FFVs which allowed companies to claim that FFVs used far less fuel per mile driven than the standard gasoline vehicle. This enabled some car manufacturers to rely heavily on a “technology” that cost very little, while still meeting the MPG targets. Beginning in model year 2016, manufacturers had to start calculating FFV emissions using actual data on E85/gasoline sales or use, rather than assuming all drivers are opting for the ethanol fuel.

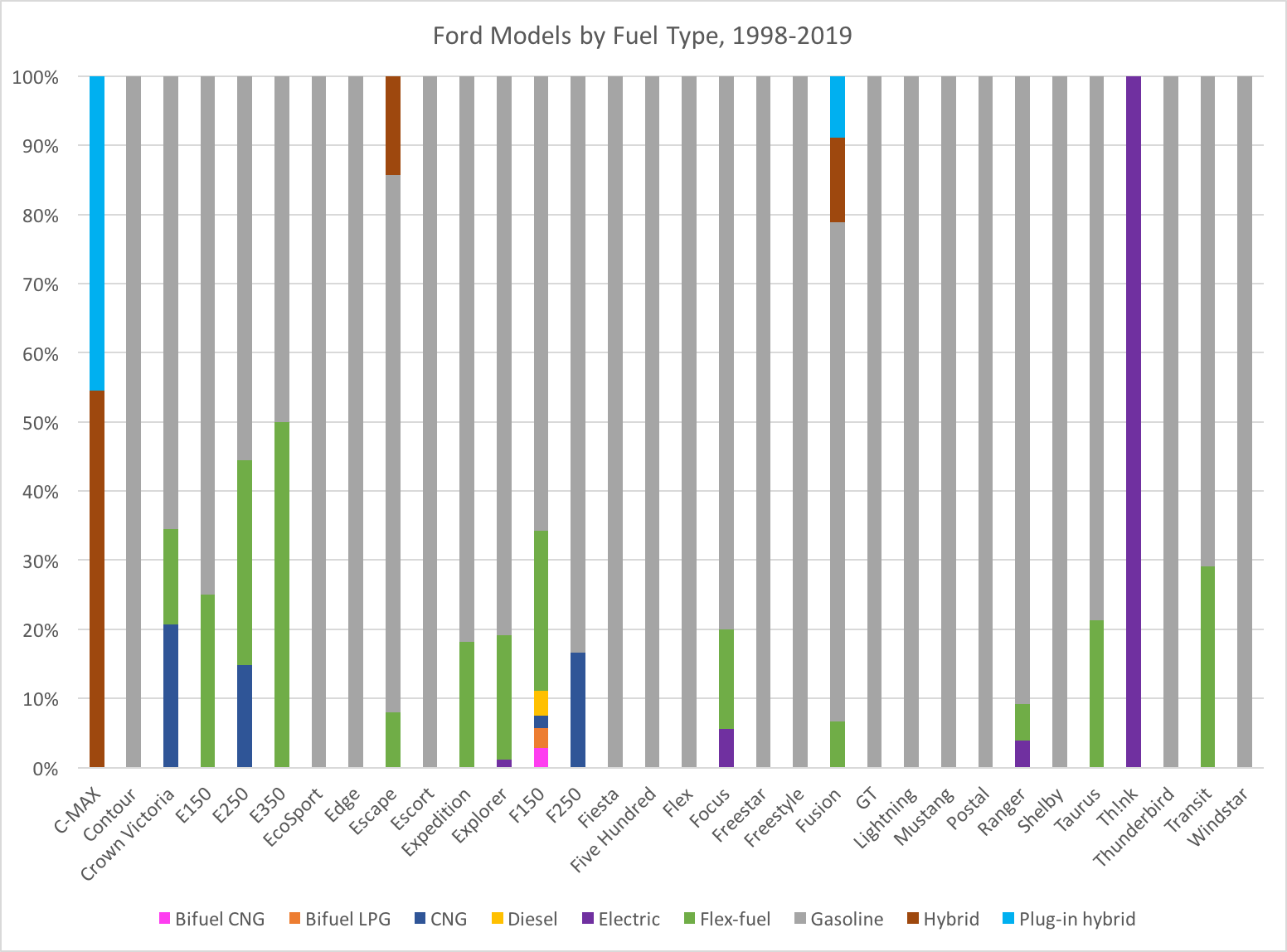

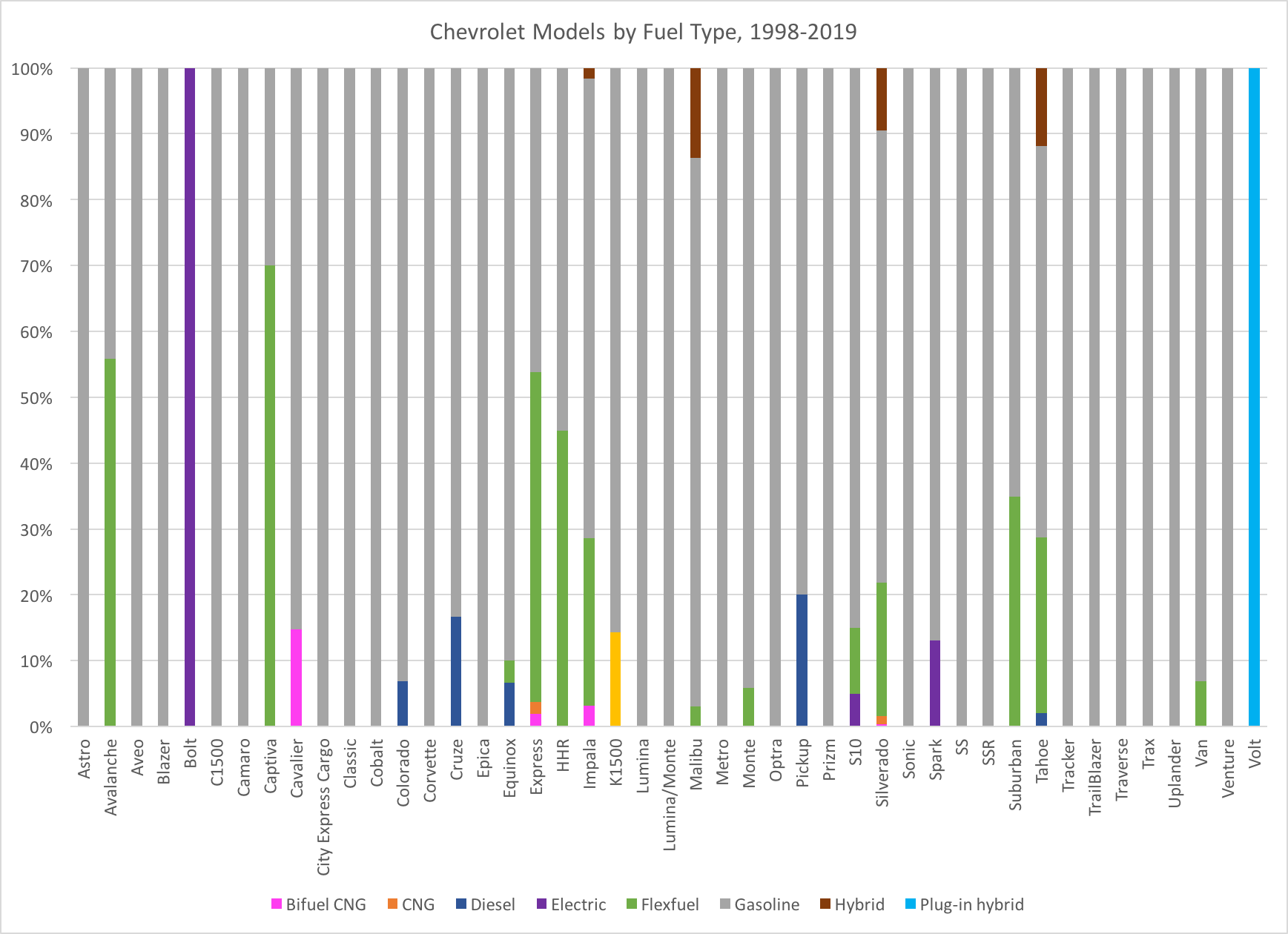

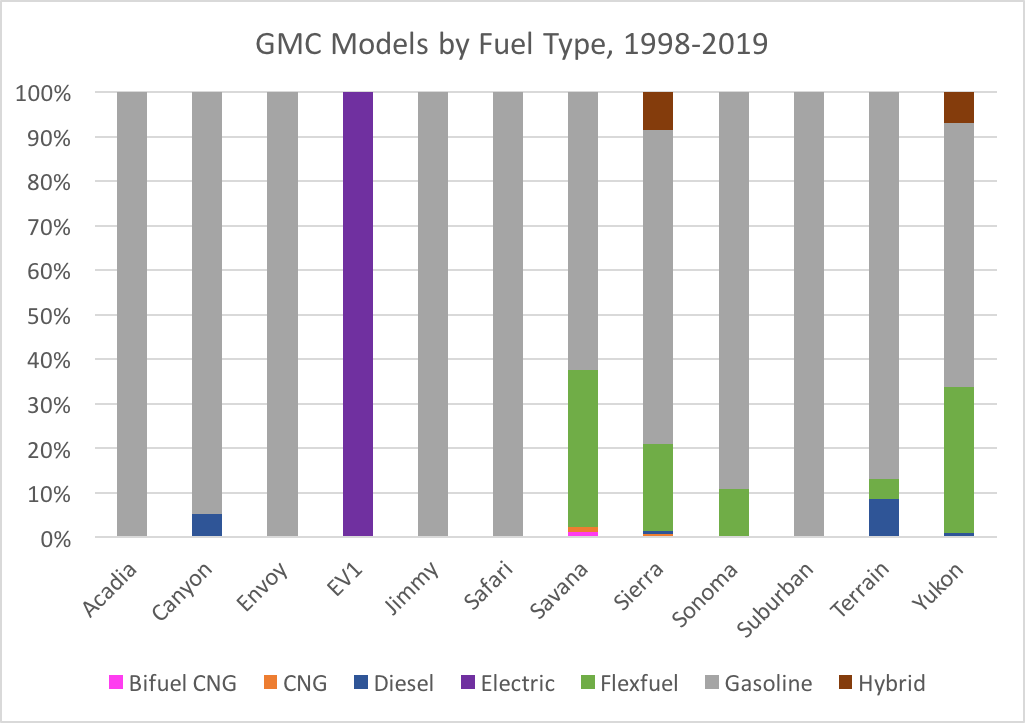

It would appear that Ford, GMC, and Chevrolet have relied heavily on FFVs in their product portfolios, but it is interesting to go a little deeper and understand which alternative fuel technologies were used on which models. Below we see that some of the largest models, particularly the pick-up trucks, were FFVs.

Fast-forward to last year. In the graph below we see that in 2018, American car makers were still producing a fair number of FFV models, with some shift into hybrid or plug-in EVs.

Data source: Alternative Fuels Data Center

Data source: Alternative Fuels Data Center

To summarize, companies were able to leverage FFV technology to meet MPG targets with little to no investment, and relied on it heavily for some of their largest models. Customers can run the vehicle on ethanol blends up to 85%, but we can assume most were not. A few other alternative vehicles show up, such as compressed natural gas or propane, however these other technologies were pricey and without significant fueling infrastructure, they would be confined to organizations that manage their own fleets, such as the delivery operations.

Electric vehicles re-emerge

Renewed interest in EVs arose from many different factors, not least of which was improvements in technology that drove down costs, high gasoline prices shortly after the economic downturn, and the introduction of new, exciting car companies like Tesla and Fisker. At a time when US automakers were facing extreme challenges, it seemed like the general population was shifting their interests in to smaller, more efficient vehicles…vehicles that, in general, cost much less to operate (while also costing much less and providing a smaller margin to manufacturers). Although EVs have remained a relatively small fraction of the overall light duty vehicle fleet, their adoption is rising at increasing rates.

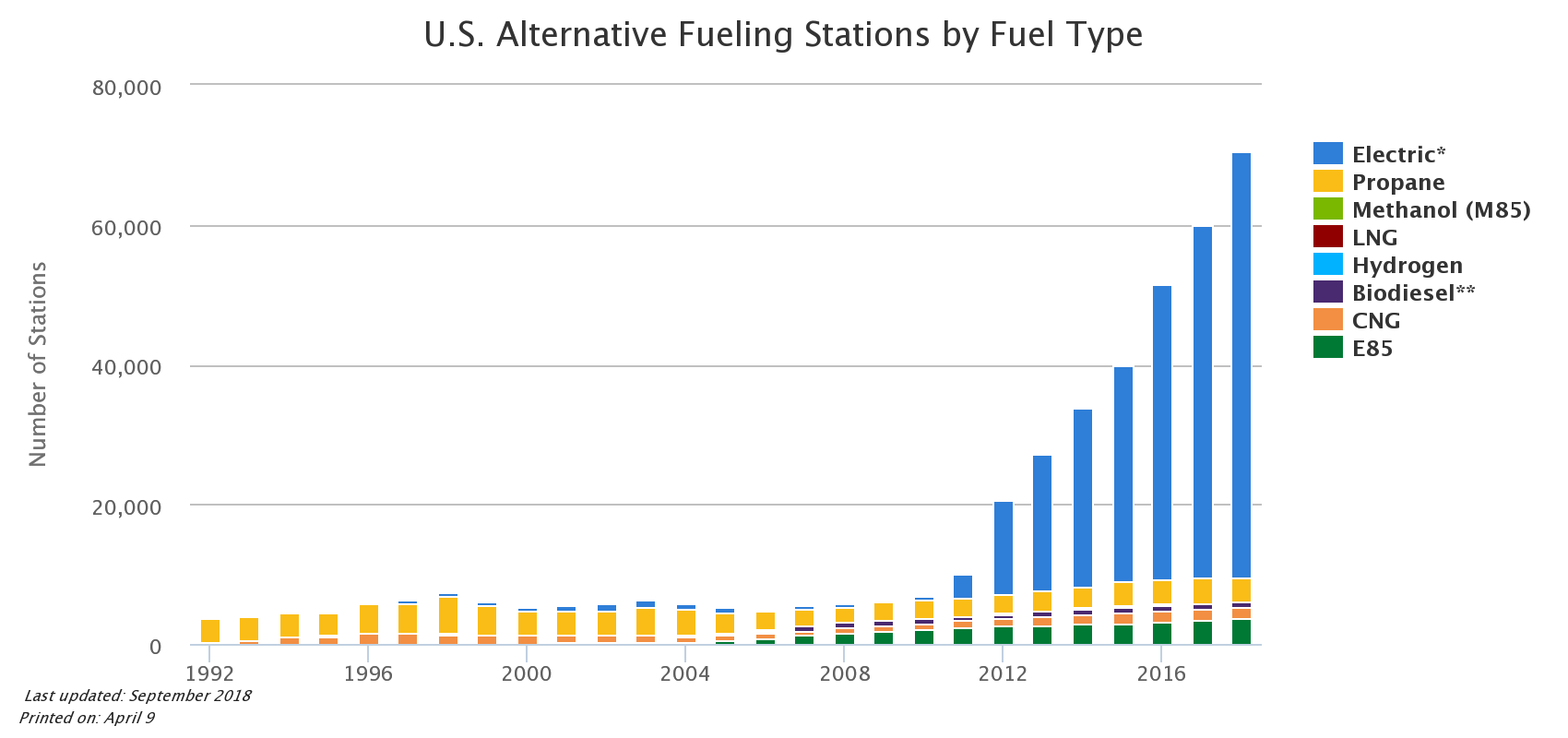

According to McKinsey, global automakers will introduce 340 electric and plug-in hybrid electric models between 2018 and 2021, and adoption is taking off in some countries, with ambitious targets in place in China and several European countries. While there is a considerable way to go before widespread adoption in the U.S. can take place, there is certainly momentum. Current EV charging infrastructure is increasing rapidly, and is widely available already, as the figure below shows.

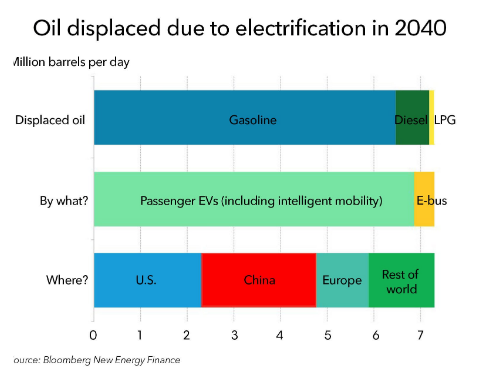

The chart below from Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF) projects the oil products displaced globally by EVs by 2040. The US portion is estimated to be 2.3 million barrels per day of gasoline, which is substantial given that our current gasoline demand is around 9.3 million barrels per day. BNEF also projects that by 2025, EVs will make up 11% of new passenger vehicle sales, increasing over time as EVs become cheaper than internal combustion engines (ICEs) by 2030. That turning point will be critical: As soon as the cost of EVs matches that of an ICE vehicle, EVs will become ubiquitous. Once the population grows less anxious about range and the realization hits that drivers may never need to visit a fueling station again, except for recharging on long trips, EVs will start to look pretty attractive to far more drivers.

Tailpipe considerations

But before we get all excited about the global momentum for EVs: Is an EV better for the environment, more than an efficient ICE? I often see or hear the argument that an EV is no cleaner than an ICE if it is charged using a coal-based electricity supply. The short response to this is EVs are better for the environment from a tailpipe emissions standpoint. If we step back and reflect on what a car is, each vehicle runs it’s own miniature power production plant, and ICEs are approximately 20% efficient, meaning that only 20% of the energy in a gallon of gas is actually moving the vehicle forward. Adding to that the lifecycle emissions of producing and refining the fuel in the first place, things get pretty carbon intensive pretty quickly.

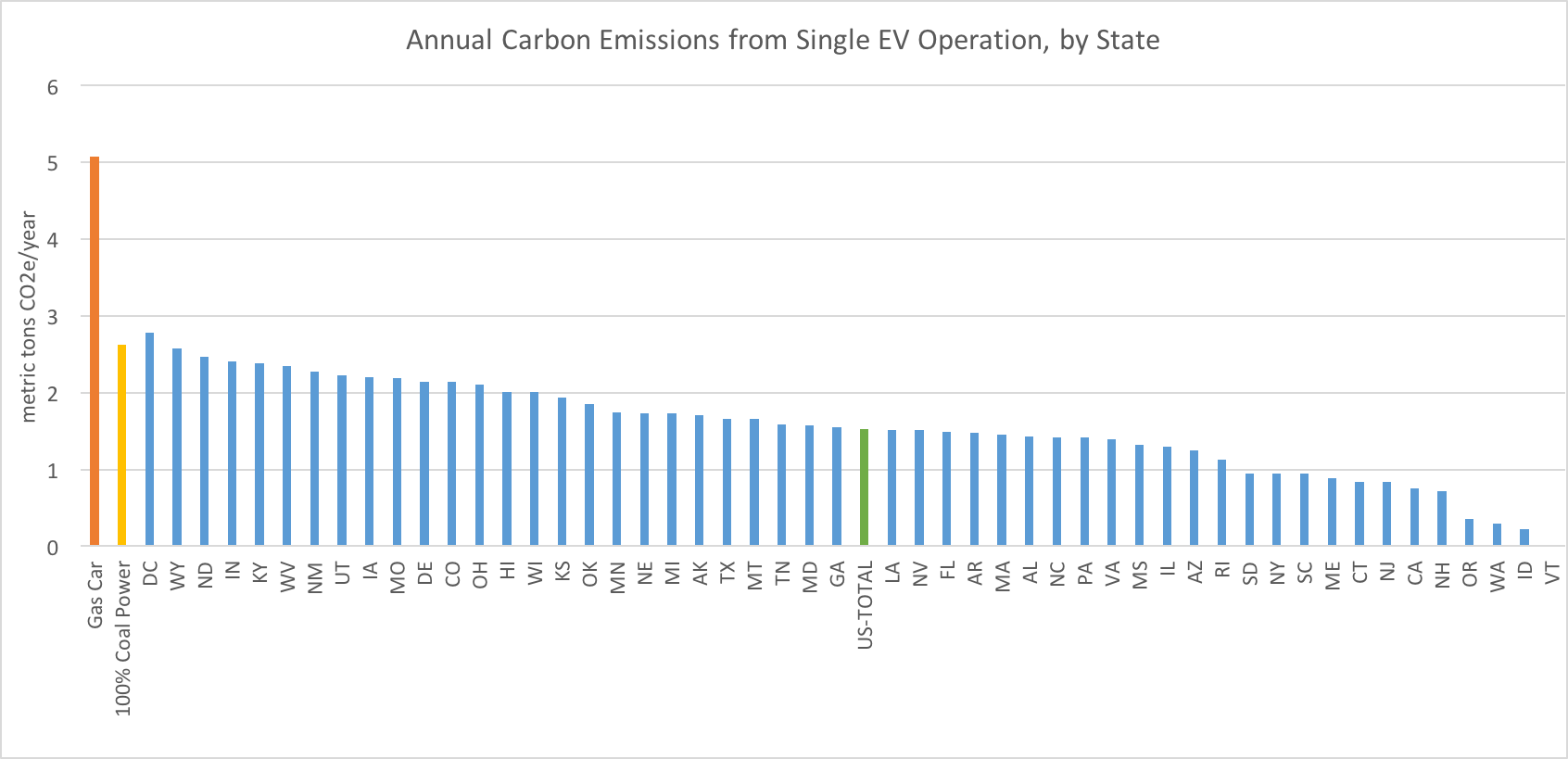

If we instead think about an EV, which is fueled through a battery charged by a power plant, we see that the efficiency per mile improves. Power plants have efficiencies ranging from 33% for coal to closer to 45% for natural gas, there is some added loss as electricity is transmitted, and the conversion of power from the battery to the wheels is approximately 90% efficient. But how does the efficiency translate into carbon emissions, when taking the different fuels into consideration?

Assumptions: 10,000 miles driven/yr; Fuel Economy: 22 MPG, gasoline; 3.9 miles/kWh (Nissan Leaf: 3.95, Tesla Model S: 3.94), EV.

Data Source: EIA, Cleantechnica

Assumptions: 10,000 miles driven/yr; Fuel Economy: 22 MPG, gasoline; 3.9 miles/kWh (Nissan Leaf: 3.95, Tesla Model S: 3.94), EV.

Data Source: EIA, Cleantechnica

Depending on the fuel mix in any given US state, the carbon intensity of a kWh of electricity will differ. It will even differ by time of day, since, for example, the mid-day power in states with high penetration of solar will be very low carbon, while the power in the middle of the night will likely come from the base load provider, which is often coal, gas, or nuclear. The key takeaway from the graph above, though, is that no matter where the power comes from, coal included, the carbon emissions of an EV are lower than a gasoline vehicle.

Another pretty significant feature to note is that the fueling costs for an EV are about a quarter that of a gasoline vehicle that is driving the same annual distance, assuming that charging is done at the average utility retail rate. In some cases, this difference may be enough to compensate for a more expensive vehicle. As EV adoption accelerates we may see some increase in fueling costs, but it does not seem reasonable that it would match the scale of $3/gal or so where gasoline currently stands.

Bringing it all together

It is difficult to separate and understand what weight each interest has had on the current and future vehicle products on offer. It seems safe to say, given all of the information presented above, that the ongoing tug-of-war centers around regulators and car manufacturers. As would be the case for most firms, when presented with a set of increasingly stringent regulations, the firm will analyze all potential means of meeting those regulations and will choose the option that results in the lowest cost, and maybe only the lowest cost in the short term. Few managers would volunteer to be the one to choose a costly, long term strategy especially in an uncertain regulatory environment like this one. There is no guarantee that the targets outlined in a regulation are implemented as written, since they are periodically reviewed.

The current administration has put on hold any additional increases in fuel economy targets. While one might think this would be welcome news to some stakeholders, when the announcement was made in August 2018, car manufacturers were not pleased. Some speculate that this reaction arose because halting fuel economy improvements goes against car companies’ increasingly eco-oriented marketing. These companies may also want to distance themselves from the current administration. And while federal fuel economy standards may have been put on hold, California is moving forward with stricter requirements for cars sold in the state, which means many car companies will be required to pursue fuel economy improvements as they initially intended (assuming that the federal government does not stop it).

While CAFE standards and product margins have influenced the products on offer in the past, consumers’ growing interest in EVs and the rapid installation of charging infrastructure could result in the introduction of more EVs, regardless of the regulations on manufacturers. This is particularly true if federal and state EV and PHEV incentives remain in place and consumers are educated on those options.

Conclusion

There is some serious momentum behind the EV movement, and while no one can predict the future, given the current automaker plans and technology improvements, it seems that EVs will continue to hold a larger and larger portion of the total fleet in the US, regardless of the short-term future of the CAFE standards. They are cleaner, cheaper to operate, require less maintenance, and are in many ways easier to fuel. For all these reasons, there are also a lot of concerned interests and livelihoods at stake should EVs persevere; but at the same time, many new opportunities will arise. As the infrastructure continues to expand, as technology prices continue to fall, and as global adoption increases, the EV movement will shift from nascent to mainstream. Even oil companies seem to be recognizing the shift, and have begun adding charging infrastructure into their long term strategies. It will be an exciting next few years in the transportation space as innovation and new technologies make their way onto the roads around us.