Renewable Energy Certificates - How Texas Wind Power Gets to Pennsylvania…or Anywhere Else

If we think back to high school chemistry or physics, you might recall that power is made up of moving electrons. Many different forms of energy, whether that be a magnet moving through a solenoid, coal burning in a furnace, or a wind turbine spinning in the breeze, can generate a flow of electrons, moving power from the generation source to the customer. If all of these sources are exactly the same on the electron level, how then are electrons generated from dirty, brown power differentiated from those generated from clean and green power? How is it that we can distinguish between physically identical electrons?

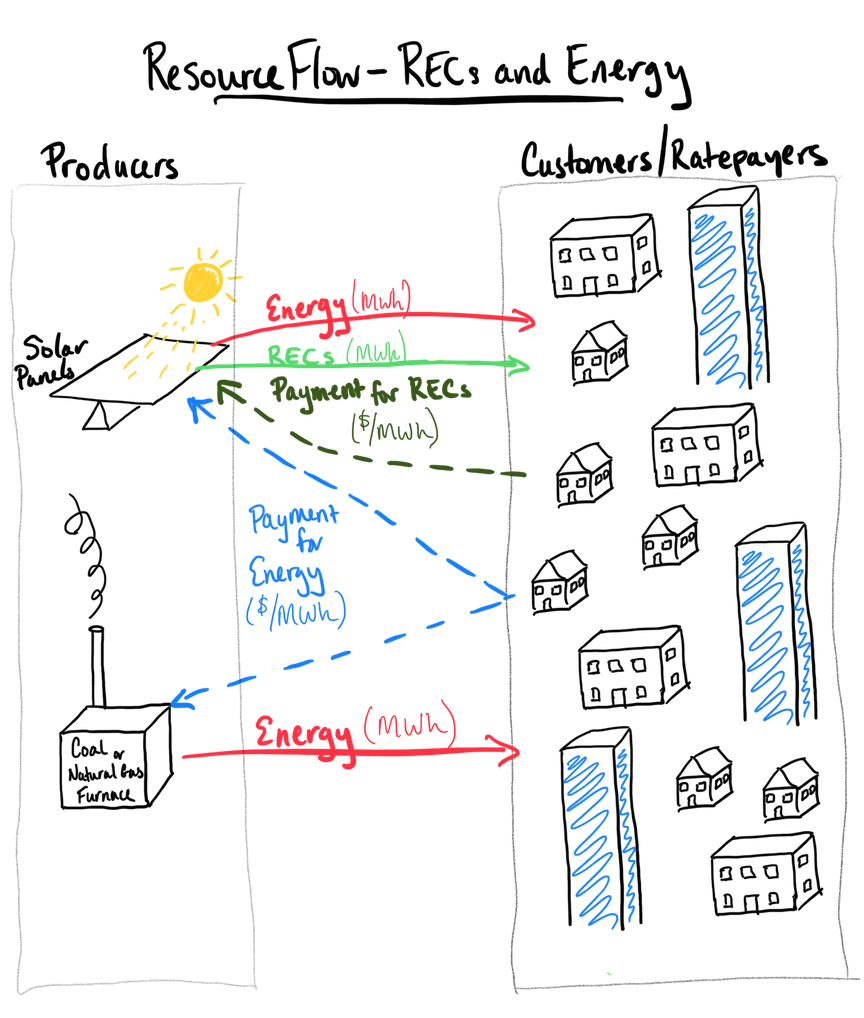

The answer is through Renewable Energy Certificates or Credits (RECs). With each unit of energy generated through renewable means, an REC is also generated in order to track and document the energy as renewable. While the units of energy that you and your household consume are likely on the order of kilowatthours (kWh), these RECs are generated on a scale one-thousand-times that, or megawatthours (MWh). The RECs are what define the green attributes of the power, and they can be sold with (bundled) or without (unbundled) the power that generated them. Oftentimes a utility or company will have an interest in the green attributes of the power they purchase, and thus they will purchase both the MWh of energy as well as the MWh of RECs. However, in cases where the supply of renewable generation is much higher than the demand, excess RECs are generated. Customers on those regional grids may not care about the fact that the power generated in their region is renewable, and thus may not be willing to pay for the RECs when they buy the power. This opens up those RECs to be purchased by others, sometimes outside of that regional grid altogether.

Who Buys RECs?

One of the largest customer groups interested in purchasing the renewable attributes along with the power are utilities, oftentimes because they are required to meet Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS) requirements set forth by the states in which they operate (click here to see all those targets, by state). RPS requirements compel utilities to purchase certain amounts of renewable energy, where details like the amount and which technologies count are left up to each state. Below is a table depicting a handful of states and their targets.

| State | Established | Renewable Requirement | Cost Cap |

|---|---|---|---|

| California | 2002 | 33% by 2020 40% by 2024 45% by 2027 50% by 2030 |

Determined by CPUC |

| Colorado | 2004 | 30% by 2020 (IOUs) 10% or 20% for municipalities and electric cooperatives depending on size |

2% |

| Florida | None | ||

| Illinois | 2007 | 25% by 2025-2026 | 1.3% |

| New York | 2004 | 50% by 2030 | None |

| Ohio | 2008 | 12.5% by 2026 | 1.8% |

| Pennsylvania | 2004 | 18% by 2020-2021 | None |

| Texas | 1999 | 5,880 MW by 2015 10,000 MW by 2025 (goal achieved) |

3.1% |

| Virginia | 2007 | 15% by 2025 (voluntary) | None |

-

Cost Caps, where applicable, limit the increases in ratepayer bills

-

Texas consumed 41,000 GWh (1 GWh = 1,000 MWh) of electricity in September 2018. Using the 10,000 MW (10 GW) of target installed capacity shown above and assuming a 50% efficiency (likely a high estimate), Texas’ renewable target generation comes out to 3,600 GWh for the month, or 9% of all generation (10 GWx30 daysx24 hours/dayx50%). In 2017 Texas reported that it had far exceeded the target, operating 26,045 MW of renewable generation, representing 23% of all generation. (26 GWx30 daysx24 hours/dayx50%) Update: Texas produced 30% of its power from carbon-free resources in 2018. Of that, 10.9% was nuclear.

In these cases, the RECs, called compliance RECs, have considerable value and typically must be purchased within the region where they are generated. Because of that, the utility often enters into long-term contracts with the energy producer to buy both the MWh and the RECs, and there is a market for procuring additional compliance RECs if more are still needed for balancing. Recently, similar agreements have been of interest to a growing number of public and private companies – businesses eager to green their supply chains through procuring renewable power. Large companies have significant demand and enough negotiating power (and relatively certain long-term cash flows) to enter into power purchase agreements (PPAs), which are essentially contracts to purchase the power and the RECs from a given supplier for an established price or under established terms.

The important idea here is that when a company or utility signs a contract with an energy producer, they are ensuring that producer has a customer over the long term, often at a set $-per-MWh rate. Recently, wind projects have been securing PPAs at around $20/MWh. Such certain cash flows allow renewable energy project developers a lower level of risk when executing a project: If the developer knows the price they will be getting for their product, the risk of potentially not generating the cash flows needed to make payments to investors and to end up NPV positive are much smaller. If a developer does not have their production contracted, they may have to sell it onto the open market, which, depending on the market conditions, could be less than ideal. Put simply, dealing with energy price uncertainty raises the risk of the project, raising the cost of capital for the developer, making the project as a whole more costly and less attractive to all involved.

Where the Leftovers Go

If a developer is not able to sell all of the RECs generated by its energy production to its customers to meet RPS requirements or the renewable energy needs of contracted business customers, it can enter those RECs into the open, voluntary REC market. In contrast to the regional market where the energy itself is sold, this market is national, meaning that RECs generated in Texas can be purchased by someone in Maine, even if the electrons cannot get there. The customer of those RECs then would continue to purchase the same power they always had, potentially of uncertain renewable composition, but would also be purchasing the RECs produced by some generator located elsewhere. That customer could then claim that they are buying renewable energy, even if the energy itself is not green. The idea behind this voluntary market is that it allows developers and operators a secondary source of income, through the sale of RECs, that could incentivize further renewable energy development, outside of what is set forth by states. RECs are produced based on technology, and some RECs may be more or less in-demand to customers. For example, a customer might be more interested (and thus willing to pay more for) an REC generated from a solar facility than a wind facility.

Current State of the Voluntary REC Market

Unfortunately, due to the supply/demand imbalance in the REC market, the voluntary REC price for wind nationwide is less than $1 per MWh. Despite the market being less than transparent, data suggests that this low price is how things have trended over the past several years, as renewable energy development has increased. Below is an example of what this cash flow might look like for a wind developer:

Assume that a developer is planning to build a 100 MW rated capacity wind farm, which is considered in the industry to be a large scale project. The upper limit on efficiency of a wind turbine is 59% (called the Betz Limit), so assuming an efficiency of 50%, close to the Betz Limit but not quite there, across the whole farm, 50 MW would be generated in an average hour of a given year. Multiplying by the number of hours in a year (8760), we end up with a total energy output of about 438,000 MWh. Using our $1/MWh conservative wind REC price, this would mean that this example wind farm would be generating $438,000 in additional cash flow in a single year.

Recent studies have shown that average wind PPA pricing has fallen to around $20/MWh, so purely for comparison, a $1/MWh wind REC price corresponds to 5% of the cash flow generated from a PPA. Also, remember that RECs sold in the compliance market go for much higher prices. Because it is also not a transparent market, the most recent data I was able to find was from 2015, and suggested that depending on the region, the compliance REC price could range from $8/MWh to $50/MWh.

One last note on the REC market: Due to the range of prices for RECs of various technologies (i.e. wind has a different REC price than solar), there is an opportunity for arbitrage. For example, because the price of a solar REC is higher than that of a wind REC, if a customer is interested in only the green attributes of the power and is not concerned with the technology associated with it, the developer can sell the solar RECs on the market and buy wind RECs to cover the customer’s needs and generate some additional income. In my analysis here, I have focused only on wind RECs, since most of the products offered to customers are derived from wind.

RECs and the Average Consumer

So what does this mean for the average consumer? In deregulated states, retail customers can choose to procure their power from a list of different providers in their area. As part of this option, there are often many products that offer 100% renewable attributes. “Customer Choice,” as this is often called, means is that the typical household could shop around for their power, which allows for greater rate competition. It also results in a wider variety of products: Variable or fixed rate products, and green products with varying percentages of renewable content, sometimes with differentiation between in-state and out-of-state generation. If the average consumer chooses one of the green products, more often than not the product is provided through voluntary RECs.

But does that mean your power is really green, and is that really doing as much good as the marketing suggests? My next post will dive into this question.

I am always trying to learn and improve. If you have any suggestions, corrections, ideas or other comments, please reach out to me at sustainabilityinthebalance@gmail.com